Riemerellosis is an infection of palmipeds and turkeys caused by Riemerella anapestifer, formerly known as Pfeifferella, Pasteurella or Moraxella anapestifer. Described in 1932 and brought to light in the early 1970s in France, it has become in recent years a dominant feature of the pathology of palmipeds, causing significant economic losses.

The disease agent and its pathogenicity

- R. anapestifer is a Gram-negative, non-spore-formed, immobile and flagella-free bacillus, 0.3 to 0.5 µm in diameter and 1.0 to 2.5 µM in length. The bacterium requires an anaerobic culture medium.

- The agent is not very resistant in the external environment. It is sensitive to common disinfectants. In the absence of disinfectant, R. anapestifer persists for 2 weeks in water and 4 weeks in bedding.

- There is an R. anatipestifer-like virus, Coenonia anatina, which differs in its biochemical characteristics but is clinically identical. Bacillus sphaericus has also been isolated in riemerellosis-type syndromes. Currently, there are at least 21 serotypes.

- There are wide variations in pathogenicity depending on the strain involved. Several serovars are often present simultaneously during an infection.

- The germ enters the body by the pulmonary route or by the transcutaneous route, during lesions: leg wounds, debeaking, biting insects, stinging, mucosal lesions. The pathogenicity seems to be more limited when the germ enters through the lungs.

Epidemiological data

Riemerellosis mainly affects palmipeds, especially mulard ducks. Rare cases are described in turkey, sporadically in chicken, pheasant and quail.

It typically affects ducks between 1 and 8 weeks of age. Incubation lasts between 2 and 5 days. Animals under 5 weeks of age usually die 1 to 2 days after the onset of clinical signs. Older animals can resist longer. Cases are rare in adults.

The sources of contamination are infected animals, sick or healthy carriers, and wild birds, which would constitute a reservoir. Carrying R. anatipestifer in the respiratory tract of ducks appears to be extremely common, even in clinically perfectly healthy subjects. The bacteriological status of a group of ducklings cannot therefore explain the onset of a clinical episode on its own and the role of an environmental or infectious cofactor must be considered.

The disease often occurs as a result of triggering factors: immunosuppressive infectious disorders, degraded sanitary conditions (wet outside areas, confined and humid atmosphere, overdensity, multiple batch system, poor climatic conditions, etc.), stress (transport, vaccination, force feeding,…).

Clinical manifestations of the disease

Symptoms

The main symptoms are : animals no longer moving, crawling with their legs backwards, head tremors reversed backwards, breathing difficulties with marked inspiration, whitish diarrhea, arthritis. Lameness, nasal and ocular discharge, a greasy cough, growth retardation with heterogeneity of the batch, lack of feathering can also be observed. Sick animals wither away and eventually die within a few days. Death can also occur suddenly before symptoms appear. An affected batch generally has significant morbidity and a mortality ranging from 5 to 75%.

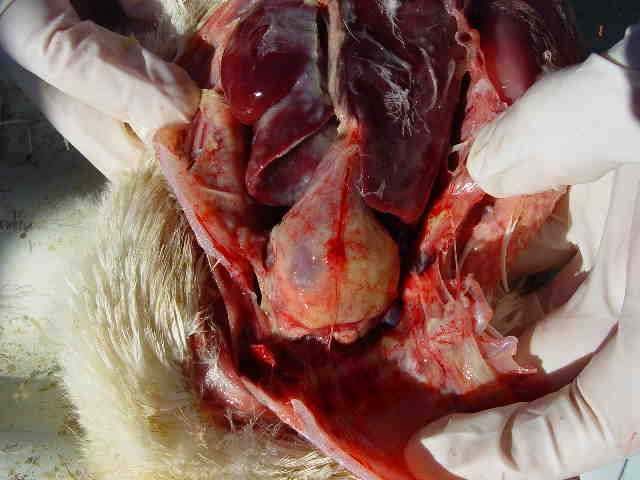

Lesions

The lesions are associated with acute or chronic sepsis and are mainly nephritis and pericarditis, which may be associated with perihepatitis and aerosacculitis. Salpingitis with the presence of caseous exudates and meningitis may sometimes be present.

Mild cerebral hematomas can be visualized. Aerosacculitis evolves into a fibrino-caseous organization. The pericardium is opalescent at the beginning of its evolution and then becomes a dry pericarditis with a caseous appearance. The spleen is slightly enlarged, elongated, with possible mottling, and often discoloured. In the terminal stage, all organs are taken up in mass by the fibrin.

In chronic infections, localized skin and joint damages can occur, such as necrotizing dermatitis in the cloaca.

The diagnosis

Clinical and lesional diagnosis

Makes it possible to establish a suspicion, but the diagnosis of certainty requires the use of bacteriology. It is then preferable to take samples from live animals.

Laboratory diagnosis

Isolation of the germ on specialized media (blood agar) is quite delicate. Culture failures are not uncommon and slow growth leads to identification requiring 2 days.

Differential diagnosis

Colibacillosis, pasteurellosis, aspergillosis

Disease prevention and control

Treatment

Involves antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin, doxycycline, flumequine, enrofloxacin, oxolinic acid, novobiocin and lincomycin), always combined with an antibiotic susceptibility test. R. anapestifer is still resistant to colistine. Its resistance to trimethoprim, oxacillin, polymyxin B and gentamicin increases. If the evolution is quick, the treatment by injection should be started, followed by treatment in water or food for 5 days. Oral treatment may be unsuccessful due to patients’ lack of appetite and musculoskeletal problems.

Adjuvant treatment with vitamins and trace elements can be considered in parallel. Patients must be sorted daily, with nursing and individual treatment.

A sufficient number of feeders and waterers must be available.

Prevention

The use of autovaccines makes overall control of the disease possible, with the difficulty linked to the multitude of serovars, or even to the antigenic variability between isolates of the same serovar. However, cases of riemerellosis occur in vaccination settings. In a context of high disease pressure, early vaccination should be carried out around 15 days. Injections are given every 4 weeks. There is no vaccine on the market.

Prevention also takes into account the elements of hygiene (farm conditions, handling, condition of bedding, gratings,…) and disinfection. For birds kept in confinement, ventilation is a major parameter to be controlled.