Duck plague is an acute and contagious disease of palmipeds, described since 1923 and long confused with highly pathogenic avian influenza. Although outbreaks are uncommon, it is a permanent threat to breeding and ornamental ducks as well as wild birds.

The disease agent and its pathogenicity

The etiological agent is Anatid herpesvirus 1, a herpesvirus of the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily. Its genome consists of a double strand of linear DNA, approximately 158 kbp.

There are strains of variable virulence, but all belong to the same serotype.

Viral particles are found in the cytoplasm, in cytoplasmic vacuoles and in the nucleus.

The virus is moderately resistant. It is sensitive to ether and chloroform, destroyed by heat (10 min at 56°C, 1 month at 22°C), inactivated at pH below 3 and above 11. Common disinfectants are effective.

In a susceptible host, the virus replicates in the digestive tract mucosa (especially in the esophagus) ; then it is found in the Fabricius bursa, the thymus, and finally the spleen and liver. The main replication sites are epithelial cells and macrophages.

The virus is capable of becoming latent and undetectable in the body ; as a result of stress, the virus reactivates and the infection can spread.

Less virulent strains are responsible for an immunosuppressive effect.

Epidemiological data

Duck plague is described in many countries. Among domestic palmipeds, it has an epizootic appearance, with a few cases per year in France. The status of wild palmipeds is difficult to know, it seems that the disease is in an enzootic state in France.

Seasonality is discussed, but it seems that clinical cases are more frequent in the spring, during the breeding or passage periods of wild palmipeds.

Only the Anatidae, Anseriformes order are susceptible (ducks, geese and swans). Sensitivity varies according to the host : Muscovy ducks seem to have a higher sensitivity ; on the other hand, wild ducks (Anas genus) seem less susceptible to clinical expression, and have the viral reservoir profile.

Contamination is direct by contact with an infected bird, or indirect from the contaminated environment. (Contaminated water plays a major role) Vertical transmission is discussed, but seems possible. An infected animal excretes the virus in nasal secretions and faeces intermittently and for several years.

Episodes in domestic ducks are often related to the proximity of a body of water where wild ducks are housed and to the contact of wild palmipeds with wild palmipeds. Avifauna is suspected of being a reservoir of the virus and contaminating livestock.

Clinical manifestations of the disease

Incubation is short (3 to 7 days). It varies according to the age of the birds, the route of contamination and the virulence of the virus.

Symptoms

The first manifestation is a significant, rapid and persistent mortality in the batch. The animals are prostrate, with their wings dropping. They have difficulty moving around with tremors. There is also photophobia, anorexia, ataxia, spiky feathers, nasal discharge, wet eyes, profuse greenish diarrhea that can be hemorrhagic. Animals are intensely thirsty and dead animals are often found under drinkers.

In breeding animals, there is a fall in egg laying and a prolapse of the penis.

Mortality varies from 5 to 10%.

Lesions

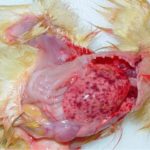

These are vascular lesions, lesions of the lymphoid organs and degenerative sequelae of the parenchymal organs.

- The carcass is congested.

- There are petechiae or bruises on many organs (heart, liver, oral cavity and digestive tract).

- Ulcers or erosions of the mucosa are found in the oral cavity, proventriculus, gizzard, a diphtheroid membrane that can cover the mucosa.

- In breeding females, ovarian follicles are hemorrhagic.

- The lymphoid organs are lesional. The spleen can be hemorrhagic, necrotic. The thymus has petechiae. The fellowship can be hemorrhagic, necrotic.

- Red haemorrhagic rings, visible from the outside, appear on the intestine and at the oesophagus-proventriculus junction. They can be ulcerated and necrotic and correspond to lesions affecting lymphoid tissues associated with the intestine.

Le diagnostic

Epidemio-clinical diagnosis

High sudden mortality, bleeding lesions, lymphoid rings in the digestive tract, presence of wild palmipeds, spring.

Laboratory diagnosis

Histology : the main histological lesions are localized and severe fibrino-necrotic enteritis with extremely rare inclusions, ulcerations of the esophageal mucosa with rare inclusions in the nuclei of the epithelial cells of the esophageal glands, and multifocal necrotizing hepatitis with rare inclusions in the hepatocytes.

Isolation and identification of the agent : the historical method is the inoculation of 1-day-old ducklings or the chorio-allantoic membrane of embryonated eggs. The virus can also be isolated from fibroblasts. The virus is identified by detection of eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions, direct immunofluorescence, or serum neutralisation.

PCR : it allows a fast (2-3 days), sensitive and specific detection. It is also of epidemiological interest. It is routinely available in France.

Serology : immunofluorescence, neutralisation, plate isolation, passive haemagglutination, ELISA. The aim is to highlight a seroconversion of birds against the virus.

Differential diagnosis

Duckling viral hepatitis, pasteurellosis, necrotic enteritis, E. coli infections, red mullet, coccidiosis, poisoning.

Disease prevention and control

There is no medical treatment. Treatments can be given for opportunistic infections.

Sanitary control

In a healthy environment, it is a matter of preventing the introduction of the virus. Beware of contact with wild birds.

In contaminated environments, it is recommended to sacrifice all surviving animals. A rigorous cleaning and disinfection protocol must then be carried out.

Vaccination

It is used as a preventive measure but also during a plague episode. The attenuated vaccine (Vaxiduck®, Boehringer Ingelheim) is administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly to animals over 2 weeks of age. Its effectiveness seems limited.